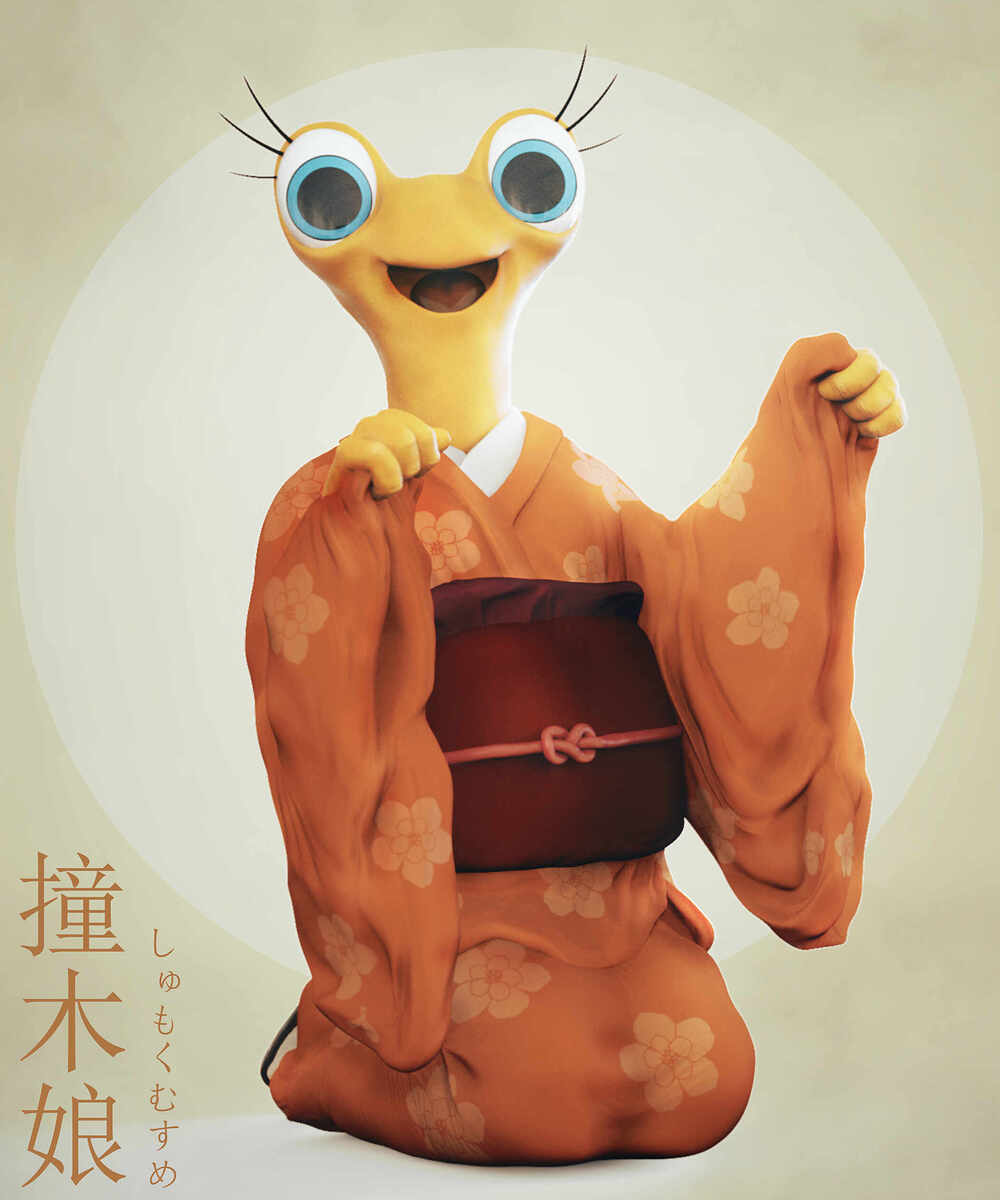

Hanzaki

鯢魚

はんざき

Translation: Japanese giant salamander (Andrias japonicus)

Hanzaki are monstrous versions of the Japanese giant salamander. These animals normally grow up to one and a half meters long, however the yōkai versions of this animal can grow much larger. They have rough, mottled, brown and black skin, tiny eyes, and enormous mouths which span the entire width of their heads. They live in rivers and streams far from human-inhabited areas.

Hanzaki and humans rarely come into contact with each other. When they do, it is usually because the hanzaki has grown large enough to eat humans or livestock and is causing trouble to nearby villagers.

The name hanzaki is a colloquialism for the Japanese giant salamander. They are called hanzaki for their regenerative powers; it was believed that a salamander’s body could be cut (saku) in half (han) and it would still survive. The call of the salamander was said to resemble that of a human baby, and so the word is written with kanji combining fish (魚) and child (兒).

Legends: There was once a deep pool in which a gigantic hanzaki lived. The hanzaki would grab horses, cows, and even villagers, drag them into the pool, and swallow them in a single gulp. For generations, the villagers lived in fear of the pool and stayed away from it.

During the first year of Bunroku (1593 CE), the villagers called for help, asking if there was anyone brave enough to slay the hanzaki. A young villager named Miura no Hikoshirō volunteered. Hikoshirō grabbed his sword and dove into the pool. He did not come back up; he had been swallowed by the hanzaki in a single gulp! Moments later, Hikoshirō sliced through the hanzaki and tore it in half from the inside out, killing it instantly. The slain creature’s body was 10 meters long, and 5 meters in girth!

The very day the hanzaki was slain, strange things began to happen at the Miura residence. Night after night, something would bang on the door, and something screaming and crying could be heard just outside the door. However, when Hikoshirō opened the door to check, there was nothing there at all.

Not long after that, Hikoshirō and his entire family died suddenly. Strange things began to happen through the village as well. The villagers believed the angry ghost of the dead hanzaki had cursed them. They built a small shrine and enshrined the hanzaki’s spirit as a god, dubbing it Hanzaki Daimyōjin. After that, the hanzaki’s spirit was pacified, and the curse laid to rest.

A gravestone dedicated to Miura no Hikoshirō still stands in Yubara, Okayama Prefecture. The villagers of Yubara still honor Hanzaki Daimyōjin by building giant salamander shrine floats and parading them through town during the annual Hanzaki Festival.

!!

!!