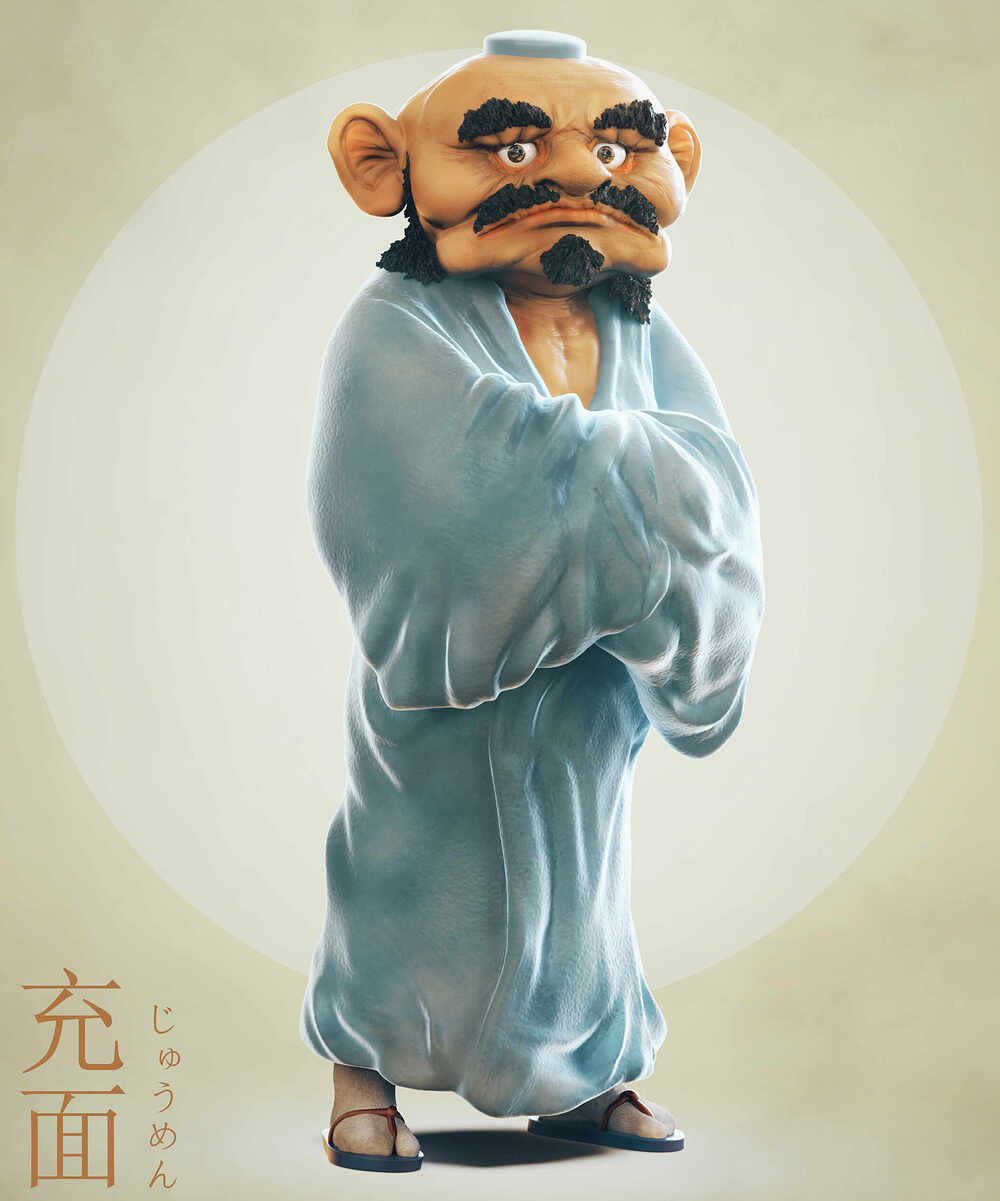

Kanazuchibō

金槌坊

かなづちぼう

Translation: hammer priest

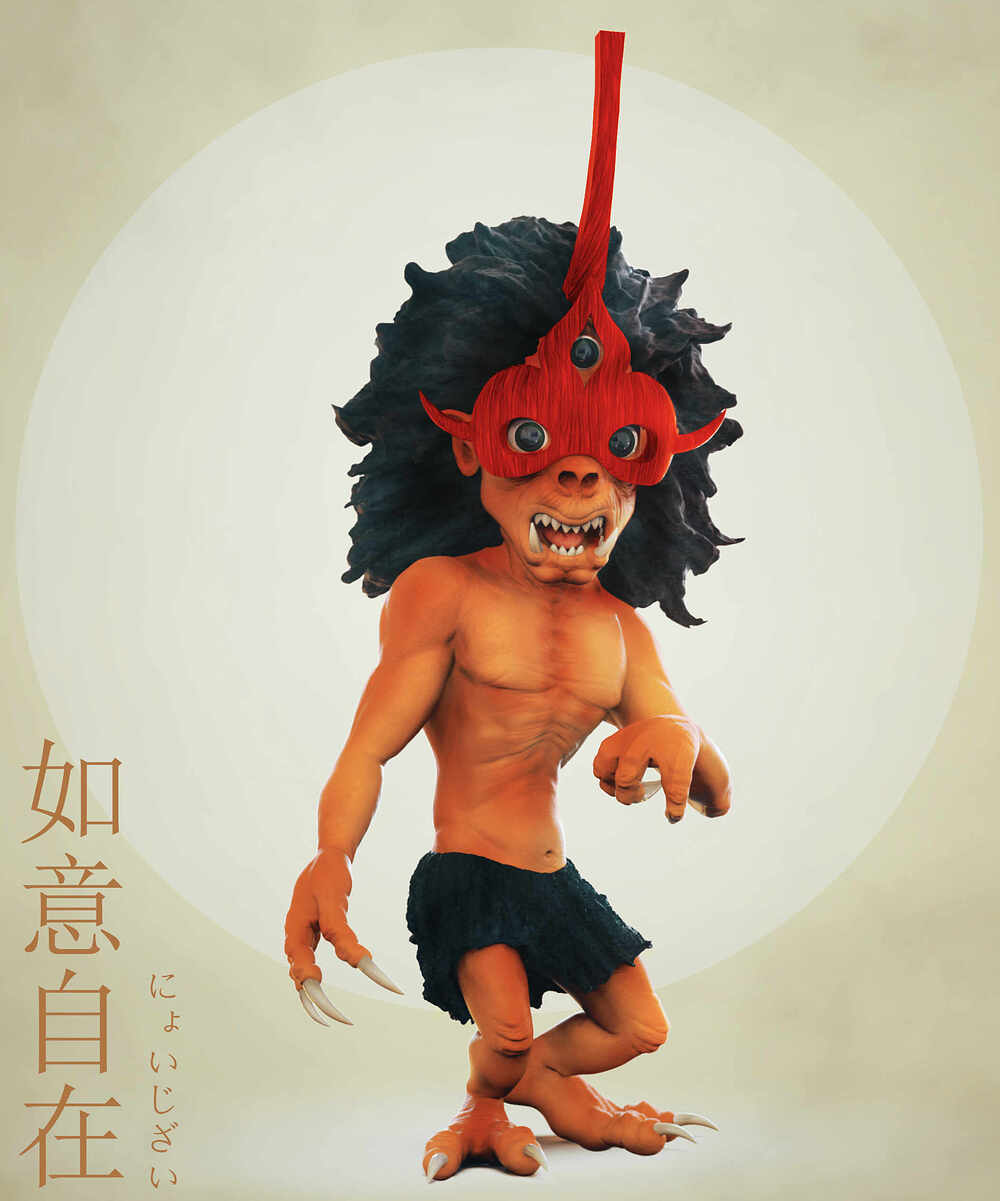

Kanazuchibō is an odd-looking yōkai which appears in some of the earliest picture scrolls. It is depicted in a number of different ways by different artists, but in most depictions it has long, flowing hair, big, buggy eyes, and a beak-like mouth. Some paintings portray it more bird-like, while others portray it in as a grotesque, misshapen goblin-like creature. It’s most identifying feature is the large mallet it carries. It is usually portrayed holding the mallet over its head, ready to strike another yōkai.

A mallet-weilding yōkai appears in many of the earliest picture scrolls of the night parade of one hundred demons. In its oldest depictions, kanazuchibō appears with no name or description. Names like kanazuchibō and daichiuchi were added much later, during the Edo period. However no description of its behavior were ever recorded. Many artists and yōkai scholars have made guesses at its true nature.

It has been suggested that kanazuchibō may be a spirit of cowardice. His posture and his hammer evoke the proverbs “to strike a stone bridge before crossing” (meaning to be excessively careful before doing anything) and “like a hammer in the water” (meaning to always be looking at the ground and watching your step; picture a hammer in a river, with its heavy head sinking below the surface, but its wooden handle floating upright). Perhaps this is a yōkai which haunts cowards, or which turns people into cowards when it haunts them.

Kanazuchibō is also known as ōari, or giant ant. In prehistoric Japan there was a culture which built large earthen burial mounds known as kofun. It has been suggested that in the Kofun people’s religion, ants were revered as divine creatures since they build earthen mounds. As the Kofun religion died out, those creatures formerly worshiped as kami grew resentful and warped into these ant-like yōkai. While it’s an amusing story, there’s no evidence to suggest the Kofun people actually worshipped ants. This explanation was almost certainly made up by modern storytellers.